Episode Four- A Letter and Two Proposals

It’s

easy to imagine the narrative of part 4 re-worked for a sitcom as it deals with

two young people whose elders are attempting to push them into marriage which,

in different ways, neither is ready for. Yet in the end the choices they make

are unexpected. The intelligent Pierre is ultimately railroaded into an engagement

proposal he doesn’t even actually make; rather it’s Vasili Kuragin who

congratulates him and his own daughter Helene on it! He is less successful

though with his son Anatole whom he tries to interest Maria Bolkonskya in only

for the marriage to be rejected by her. While the episode starts with alot of material that seems like old fashioned frippery, it’s very cleverly constructed contrasting the two

situations and held together by Basil Henson’s wonderfully arch expressions.

Neither couple are ideally suited. Helene is beautiful and poised but Pierre believes she has no brain. Maria is plain but practical and has no connection with the vain Anatole who in any case is more interested in the French maid. Internal monologues comes into play as well and work so much better here than last week’s unexpected battlefield musing. We hear Pierre constantly saying to himself “how did this happen?” while Maria concludes that she wants to be happy and knows she would not be with Anatole. It is of course a timeless plot that had been and will continue to be re-purposed in all manner of dramas.

It is fun to see Pierre mumbling and fumbling like a gawky adolescent with Anthony Hopkins’ busy acting coming to the fore again. Angela Down’s stillness also works well against Colin Baker’s haughty self interest as Anatole. The letter referred to in the title is a note from Nikolai outlining the events of last week for which he appears to have been promoted. This really does tip over into over the top drama as the family react in various ways; whether happy or sad they appear to be playing to a gallery some distance away.

Episode Five- Austerlitz

Strategy

is what this is about as events take place entirely out in the field as the

inevitable battle draws near. Though both sides use identical overtures-

sending a high ranking envoy to exchange diplomatic niceties while also scoping

what the opposition camp is up to- it is clear Napoleon is much better at this

sort of thing. He manages to convince the Russians that the French army are

underprepared and short handed while his envoy gets the true measure of the

intent of the Russian camp. What the drama also does is paint a portrait of

each side’s leader. So we see Donald Douglas’ younger Tsar whose enthusiasm for

the campaign is not matched by intellect. He tours the battalions hoping his

presence alone will be enough to inspire the troops. We see the fervour he inspires in the

form of Sylvester Morand’s Nikolai Rostov whose tall tales from the battlefield

are called out by Bolkonsky. Yet these are really tales of what he wants to achieve

and later gets himself transferred to the front line. It sums up how

the Russians are more enthusiastic than they are skilled

David Swift’s Napoleon lingers in his tent sending equally inspirational messages on paper while he spends his time more

valuably working out what actually needs to be done. The narrative paints Napoleon as a

brooding figure, often alone in the semi darkness as he pours over maps while

his keen understanding of strategies is clear from his battle meetings. He allows

his Marshalls leeway knowing their skills can win the day whereas we see the

Russian meeting outlining intricately planned detail as if they can control

what both sides will do.

This

occurs to Andrei Bolkonsky who, in one of the increasingly well placed inner

voice monologues, realises the strategy sounds wrong. Later on the battlefield

he seems to comprehend that the Russians have been outflanked long before the

crusty Kituzov (Frank Middlemass as his bellowing best). It’s a good episode

for Alan Dobie actually- during this meeting as he voices his thoughts he does

what the best actors can do and subtly alters his facial expressions in tune

with what we can hear.

The

battle itself is a triumph for a tv show; once again access to many hundred

extras gives a grand sense of scale - a modern viewer thinks `digital effects` but there was no such thing then. Instead there are literally thousands of extras. John Davies’ direction mixes

confident wide shots of the lines and much closer, sometimes hand held, footage

of the bloody fighting. I know some have suggested these scenes are a little

laboured lacking perhaps the daredevil gymnastics we become accustomed to in

films but I would imagine they are far more accurate a depiction than the big

screen. Lines are not held, troops don’t advance all together and through

the ramshackle fusillade you can taste

the terrible toll these brutal battles took. Bolkonsky falls, a bullet grazing

his head and even though he appears dead at the end of the episode, he isn’t.

There’s a symbolic shot though of his body in the foreground and the victorious

Napoleon on a hill in the distance. Yet the latter is not triumphant and pays

tribute to the bravery of his fallen enemies.

Episode Six – Reunions

People

often say vintage tv dramas lack emotion unlike today’s which sometimes

overplay that aspect with lashings of technique and orchestral flourishes. Yet

here’s an example suggesting that’s not entirely true. `Reunions` updates us

with what’s happening in three different households and there is plenty of joy

and sorrow to go round. At the Bolkonskys despite two months since Andrei was

reported as falling in battle, his sister still holds out hope as the body has not

been found whereas her father declares that hope “is for fools”. Andrei’s

heavily pregnant wife meanwhile has not been told anything. At the Rostov’s

Nickolai’s return heralds speculation over whether he and Sonia can be together

while a new arrival, the smooth Dolohov sweeps in with a trendy moustache and

card tricks. Pierre, meanwhile, is unaware but also sort of aware his wife

Helene is having an affair with the sneaky Dolohov. If this all sounds a bit

like a soap opera set in the past, it is given more weight by some exemplary

acting especially from Fiona Gaunt’s distant but clever Helene and a great turn

from Donald Burton as Dolohov.

The

scenes are immaculately arranged from the dimly lit cold, lonely corridors of

the Bolkonsys as they wait to the warmth of the Rostovs and the boisterous

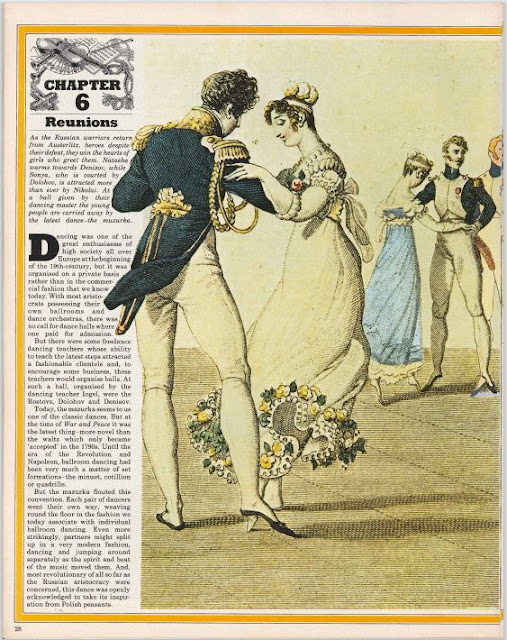

greeting the family give Nikolai. The episode’s set piece is set in a dance

where many of the characters come together for those oddly poised dances that

were all the rage. The Mazurka has to be seen to be believed; the man seems to

have you behave like a leaping deer. No wonder it’s never been revived.

Despite

its period drama trappings there is rich emotion in nearly every scene from

Helen’s dismissive responses to Pierre, Prince Bolkonsky’s refusal to even

think his son has survived, Sonya’s responses to her potential suitors and

Dolohov’s angry look when he doesn’t get his own way. With a melodramatic flair

that you probably would get today Andrei turns up, robes covered in snow, at

the moment when his child is born but his wife dies. Without music and set

amidst flickering candles it’s proof that these dramas can do emotion just as

well as they can today.

Episode Seven- New Beginnings

In

which Pierre joins the Freemasons, a ritual depicted by a most odd assortment

of symbols and jagged music that could be part of some series about the occult.

It looks so out of place in what is actually a superbly philosophical episode

presumably much of it taken from the novel. Pierre has hit rock bottom; his

unhappy marriage made even unhappier when he suspects the rascal Dolohov is his

wife’s lover mainly because the man himself keeps goading him about it. He

finally flips and challenges the scoundrel to a duel. Considering his

formidable reputation with pistols of all kinds, Dolohov actually turns out to

be a bit rubbish at the duel itself. Shot in a very cold, snowy forest we see

both parties advancing but Dolohov hasn’t even pointed his gun. Pierre trips,

gets up and fires hitting his tormenter albeit not fatally. Rules say Dolohov

has a shot but he misses.

Like

most matters we’ve seen him involved with this still doesn’t make Pierre any

happier but his Road to Damascus moment occurs in the unlikely location of a

waiting room as he travels to Petersburg. An elderly man engages him in a far

higher level of conversation than your or I have experienced at a bus stop or a

long queue in Waitrose. This man puts Pierre onto a new way of life, of helping

others for its own good rather than the selfish life Pierre has admitted he

hates. All of which leads him to the Masons.

The

results are evident when Pierre visits Andrei with, as the latter suggests, the

enthusiasm of someone recently converted. He tries to instill some of those values

in his old friend, now living a country life having left the army, and the

episode ends without telling us whether he has been successful. It struck me

that if indeed a series did go down this sort of road, the conversation would

be more personal, more emotional. The

difference in Pierre is plain to see. At the earlier dinner where he ended up

challenging Denisov, Pierre was taut and fearful at once, Here he is enthusiastically

explaining his new idea for living yet engaging in discourse rather than arguing.

Suitably

this is also the episode where the Tsar and Napoleon sign a treaty and, as one

observing soldier drolly puts it, pin medals on each other. We all know of

course this is one new beginning that won’t live up to its promise.

Pictures from the 1972 Radio Times War and Peace Special magazine.

The Lonely

Sea

Following

recent tragic events, teenager Tom Allenby has abandoned the Earthstone which

gives him power over the elements. Yet he is soon drawn back into that world by

a threat from a three hundred year old menace long thought to be dead. As

powers centre around a Bronze Age tomb that is not what it seems Tom is thrown

into a spectacular confrontation with powers from both the Earth and the Moon. The

Lonely Sea combines epic adventure on land and at sea, ancient mysteries and

emotional journeys.

This is the

sixth novel in the Heart of the World series set in and around the remote

English village of Rooksbourne under which the world’s natural elemental energy

lies.

Available on

Amazon in print and Kindle ebook format via link below

The Lonely Sea: Amazon.co.uk: Connors,

John: 9798859399956: Books

For more stuff

on my other books there’s a website www.johnconnorswriter.com

No comments:

Post a Comment