A charming

true story

In 1961 a Newcastle man called Kempston Bunton stole the

famous Goya painting of the Duke of Wellington from the National Gallery in

London as a means to fund thousands of free television licences for pensioners

only later he was forced to return it and stood trial for the crime. If that true story seems slight this 2020 film is anything but with a script that plays as a

social commentary of the time as a well as a portrait of a man who battles against injustices using unconventional means.

Kempston Bunton , a cab driver who talks too much (that’s

not a problem these days!) is fighting a campaign for free tv licences for

pensioners. His slogan- `Free TV for the OAP`. He refuses to pay his own family licence on the grounds that having

removed the set’s coil which allows access to the BBC he should not have to. He

only watches ITV! He is even more incensed when, after his repeated efforts to

raise the issue receive rebuttal, the government pays to buy the painting. Can

this work of art help him achieve his aim? It is a flawed yet idealistic plan

which is Kempston all over. He is a true believer in what is right, in fairness

for people regardless of the law. There’s also something of Don Quixote about

him as his principles clash with the letter of the law. The tale does have a

twist though, one which apparently was not revealed until about ten years ago

and which the film deals well.

The film is totally absorbing, witty and very well played. What could have been slow and overly earnest is instead a comedy drama filled with knockout lines, social observation and an old fashioned sense of being something of a caper. It’s the sort of feature you can imagine Ealing Studios turning out back in the day. It’s shot with a real Sixties focus on dialogue and some scenes rendered using period footage montages done in that split screen manner beloved of the time. The palette is washed out and shady.

The dialogue sounds authentic enough to feel real without being too stark. Nods to sentimentality are well earned and never over indulged, there are no big scenes of revelation simply the travails of a family caught in a situation they can’t quite deal with. The splashes of wider social comment are well placed to show Kempston’s principles – his simple analogies about our interdependence may sound naïve in some respects but we could do with more of this sort of thing right now. He stands up for the right thing even though, as we see, it keeps getting him fired from jobs. He also writes plays though a note at the end tells us none of them were ever produced.

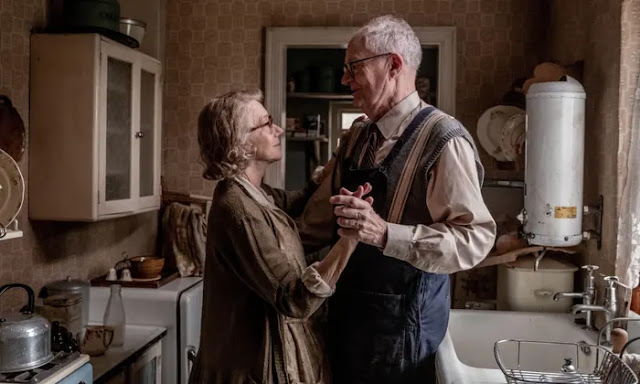

Jim Broadbent, probably the most reliably good British actor in modern cinema, is once again excellent and after just one scene you love this character. Kempston is a hard worker, but will take a stand rather than live a quiet life whenever he sees injustice. Yet he’s not bitter, he remains optimistic and loyal- whatever he does it is ultimately for his family or for the greater good. Broadbent makes you believe wholeheartedly both in the character and his beliefs. His scenes in the court room are especially funny and he has a great dynamic with Helen Mirren dowdy as you like as his long suffering wife Dorothy with a wig and pained expression but in her own way just as spirited a character.

Another actor at the top of her game Mirren notably doesn’t allow the sadness and weariness that this character has due to a family tragedy to overwhelm the film but it is always there. Dorothy admonishes her husband, yells at him but secretly I think she rather admires his way of dealing with the world. The cast also includes strong performances from Anna Maxwell Martin as a posh woman whom Dorothy cleans for, Fionn Whitehead and Jack Bandeira as Kempston’s adult sons and Matthew Goode as the solicitor at the trial who brings a theatrical swish to proceedings.

Director Roger Michell, in what turned out sadly to be his final movie, adds

some fabulous filmic touches such as the sequence when we have a point of view

of the theft and pass lots of other paintings which all seem to be looking

at us accusingly. Later, the panting itself plays a key role when one of the Duke’s eyes

pops through a hole in the back of the cupboard where it’s been hidden.

At a crisp ninety five minutes there is no fat on this

film, in fact I really wanted it to go on longer so we could spend more time with this unconventional family. The Duke sashays easily from kitchen sink

drama to farce and back and the

results are hugely enjoyable.

No comments:

Post a Comment