Episode Twelve- Fortunes of War

The rigour with which this story tackles

different aspects of war yet also seamlessly draws together the different

characters is never more evident than in this episode. Without showing us any

actual fighting the impact of the campaign is illustrated in a number of ways.

There is an impressive early shot of the French advance filmed with hand held

cameras that has a quality like news footage you’d expect in modern productions.

Almost casually the camera picks up more and more soldiers in the distance

showing the size of the invading army. Once again the modern viewer has to

remember that this is not digitally created- all those extras were actually

present. It is so authentic looking I was half expecting a reporter to be

brought into shot describing the advance!

We’re privy to a noisy meeting of Napoleon and

three of his Marshals who seem concerned about the pace of the advance across

Russia which has to date met little resistance. Instead the Russians are

retreating while burning property as they go. Bonaparte knows they will make a

stand but the others believe this strategy is stretching their supply lines to

the maximum. Oh and winter is coming as well. Here our knowledge of history

does remove some of the surprise of these developments but the skill of this

production is to frame them so they are still interesting. Meanwhile the high

ups in Moscow are addressed by the Tsar in order for them to give money and

manpower freeing their serfs to go fight in the army. It’s not that attractive

a proposition- a sequence of wagons filled with injured soldiers is shown and

they are all very young.

Meanwhile Maria and her ailing father seem

reluctant in their different ways to accept what is happening. After he dies

her shock when a bunch of peasants barge into the house where they are staying

having decided retreat is not an option throws up more issues of war. These are

I suppose the early stirrings of the later revolution. The episode ends with a

curious meeting between two characters who’s stories are linked yet who have

never met before. Maria is rescued from her palaver by Nicolai Rostov who

commands the errant serfs on his own by shouting a lot. There’s just a hint-

could the eventual marriage between the families be of different people to

originally thought. Its an episode in which Angela Down impresses as she takes

Maria through a range of emotions as matters progress.

Episode Thirteen- Borodino

“Things aren’t as simple as a row of knitting”

says Pierre as his cousin tells him about the rumours that are causing people

to leave Paris. In the city he is a voice of wisdom, a rich man whom people

listen to. Yet we see him later in a rather absurd `visit` to the area around

Borodino where battle will soon be joined and he calls on Andrei as if popping

in for tea. It is here that the latter provides an honest assessment not just

of this battle but of war in general suggests the same argument that over a

century later would be used to justify nuclear weapons. He believes war has

been turned into a ritual from which very little is gained yet thousands of

lives are lost; “we’ve made a game of it”. Instead he suggests it would be

better make war really dangerous, take away the protocol, the civility and most

wars would never have to be fought he asserts. Pierre is not sure what to say

about that.

He and we have already seen a religious

ceremony taking place in the rolling hills in a seqeunce that is rather moving.

Choral singing, flags and incense draws soldiers in from each side of the

screen we’re watching, the first of many superb directing choices in this

episode. Yet later Andrei wlll dismiss this; “Each side prays to God for

victory before the battle and thanks God for victory afterwards if they get it.

As if God cares.” Pierre is all strategy

talking of numbers but Andrei reckons it doesn’t matter so much. The side that

wants to win the most usually wins. He’d make a great football manager!

The battle itself is shown with the sort of

all encompassing style we’ve come to expect from this series. Direction and

editing seamlessly construct a fast but believable conflict using fast cuts,

hand held cameras, unusual angles and explosions that frequently blast in from

the side of the picture making them seem more powerful. The sound is terrific

too and we see some brutal moments including one alarming sight of a soldier

being blown apart. Its only on screen for less than a second. Just as effective

as the battle goes on is the close quarters fighting. So many Hollywood depictions

of this era seem to think the weapons were easy to wield but here we witness

the difficulties the soldiers have to go through just to make the bayonets effective.

Smoke drifts everywhere and there are whizzing noises like fireworks.

In the middle of all this flits the almost

comedic Pierre, desperately holding on to his velvet hat, comic relief perhaps

in the middle of all this carnage. Yet he sees for himself the true nature of

conflict a long way from the armchairs of Moscow. When he’s physically attacked

he seems to think he can shout at everyone to stop it! It is as good a

demonstration of how Russian nobility is so unprepared for this as there could

be. Once again we have a cliffhanger of Andrei’s apparent death though it looks

more final this time but it’s curious that when what looks like an early,

larger version of grenade lands at his feet he makes no attempt to get out of

the way. A final image as nighttime falls

it grows dark is of lots of still faces of those killed shown in close up, a

reminder that however impressive this staging is, there were thousands of real

deaths at this battle and an appropriate reminder of Andrei’s words and the

true nature of war.

Episode Fourteen- Escape

It is odd to note that when the series was

first shown, `Borodino` and `Escape` straddled Xmas 1972 and it’s fair to say

there is nothing festive about them. They do though offer immaculately

assembled portraits of all sides of war. Last episode was the battle, this

episode spends just as much time on the aftermath and how various people are

affected. The opening montage- which in a modern production would probably be

drenched in violins- is played with barely a word spoken, the main sound being

the spattering of endless fires on the battlefield. We join a man searching to

see who is alive as he shines his lantern on each body to check. If someone is

breathing he plants a white marker in the ground and a stretcher party will

later collect the person. We also see a glimpse of the two leaders- Napoleon

and Kutuzov, neither of whom have much to say because they both know this

massacre of both sides has been essentially a pointless operation. In his best

scene yet in the series Kutuzov outlines succinctly why Moscow must be

abandoned, refusing to accept the symbolic danger.

The really sad scenes though take place in

the Rostov’s Moscow home where they are delicately packing dinner sets and

mountains of clothes for their departure. The army have marched into Moscow at

one end and out the other; clearly showing that the authorities’ talk of

fighting the French in the streets is not going to pass. Then Natasha sees a

parade of wounded soldiers passing the house and decides to invite some of them

in. In another demonstration of how impressively this production was willing to

do anything a huge set depicting the outside of the house is seen only for a

handful of scenes. Arguments between the Count, his wife and Natasha open up

the different generations’ viewpoints- while the Countess thinks this is not

her problem and that the government should sort it out, Natasha wants to help

and in the end they do. Seeing these serious arguments shows we are wolrds way away

from the social frivolity of the opening episode.

In the midst of all this, Pierre, back from

his unlikely trip to the battlefield- rages against the authorities and decides

to stay put so he can face his destiny which he believes is linked to Napoleon.

In a way though all the characters are linked to him. Perhaps the most shocking

revelation- apart from the fact we learn at the very end that Andrei appears to

have cheated death yet again despite being listed as deceased- is when Napoleon

asks why the fighting has stopped. It turns out that both sides were too

exhausted to carry on.

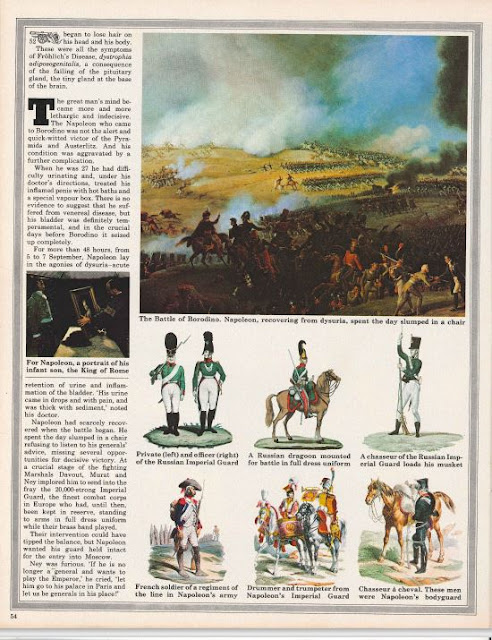

Scans from the 1972 Radio Times War and Peace Special

Why has moondust been found in a Bronze Age tomb? Where do the giant flying swordfish come from? Who is the three hundred year old cardinal? As he grieves a family loss, fifteen year old Tom Allenby is drawn into a race to stop an ancient power being released. The epic sixth Heart of the World novel The Lonely Sea available now in Kindle ebook or print format

The Lonely Sea:

Amazon.co.uk: Connors, John: 9798859399956: Books

For more on my other books there’s a website www.johnconnorswriter.com

Alt blog www.thiswayupzinealt.blogspot.com

No comments:

Post a Comment